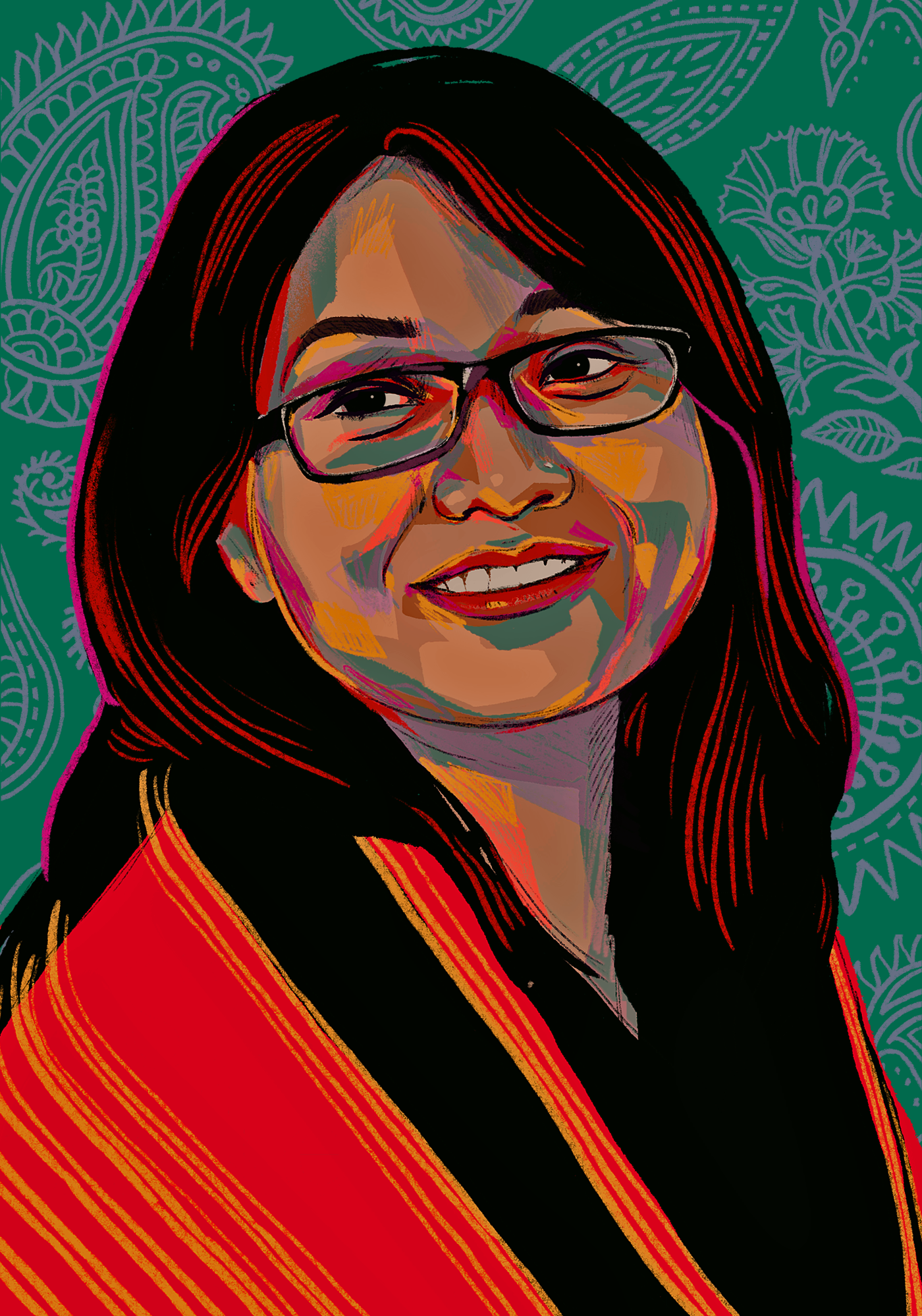

For Indigenous youth activist Chandra Tripura, neither age nor status can stand in the way of land justice. “Our Indigenous leader, [who] I call grandpa, taught me to judge based only upon the ideologies a person carries and their values,” Chandra says. “I always remind myself of this when I face difficulties and frustrations.”

These wise words of resilience fuel Chandra’s leadership in Indigenous and human rights organizations in her home country of Bangladesh. She describes her work as a “natural” service rooted in the values of her community. “Most of our values- the importance of protecting Mother Nature, the forest, the natural resources- we receive them from our cultural system, our Indigenous educational system and knowledge transfer through our grandparents.” Chandra notes that Indigenous youth are uniquely suited to lead climate solutions because of their ancestral place-based knowledge and familiarity with global climate science.

“Young [Indigenous] people care about [the climate crisis], because we step in both worlds: the new technologies while at the same time, trying our best to carry the legacy of our ancestors and elders,” Chandra explains. “We would love to carry this legacy and our culture wherever we go.”

Chandra’s fearless commitment to intersectional justice is reflected in her social entrepreneurship. In 2017, she founded the Hill Resource Center, which promotes Indigenous culture and community development in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. Chandra has also led multiple workshops for Indigenous youth on behalf of UNESCO and the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP). This work, she hopes, will empower Indigenous youth everywhere to fight for land rights, climate justice, and self-sovereignty.

With more than ten years of grassroots activism behind her, Chandra now seeks larger-scale change. “The main challenge I see [to justice] is lack of legal recognition for Indigenous communities,” Chandra says. She notes that when governments do not recognize Indigenous communities or their governance systems, they cannot utilize the resilience built into traditional Indigenous ecosystems. This, in turn, reduces the ability of Indigenous peoples to combat natural disasters and climate change at scale. “If we don’t get recognition by the state, it is impossible to bring our solutions to the country or global level,” Chandra reflects. Nonetheless, she remains hopeful for a better future.

“For peace, justice, and to make this world and our country better, states must recognize Indigenous peoples and our self-determination. Only this can ensure that we can be a part of global processes [of climate resilience] with dignity and our rights.”

At COP28, Chandra hopes that Indigenous relationships with land and land-based resources will lead to positive change. “The country processes and global processes. . . will be meaningful when they include and recognize Indigenous peoples, and our contributions,” Chandra says. “We know well how to protect and nurture the Mother Nature. Whatever we receive from Mother Nature. . . we believe that we belong to the resources, they don’t belong to us.” Yet even as Chandra recognizes the unique perspective Indigenous leaders bring to climate negotiations, she believes their perspective is valuable for all of humankind